John B Kelly, the New England regional director for Not Dead Yet, a national disability rights group focused on opposing medical aid in dying and euthanasia legislation, has become a vocal opponent to the passing of these laws.

“I myself am paralysed below my shoulders,” Mr Kelly told The Independent. “So I get to see a barrage of better-dead-than-disabled messages, as carried in such by films like Me Before You, Million Dollar Baby, etc.”

Laws relating to medical aid in dying add to this “better off” messaging, Mr Kelly said, because they create the perception that personal autonomy should be regarded above anything else. Once that autonomy is taken by a terminal illness, people sometimes think that their life is no longer worth living.

“When we look at the reported reasons for assisted suicide out in Oregonin 2019, it’s all about autonomy,” Mr Kelly said.

Oregon’s annual data showed that 87 per cent of patients who used the end-of-life option in 2019 reported a loss of autonomy as one of their main reasons. About 90 per cent said decreased ability in participating in activities that made life enjoyable was another key reason, and 72 per cent said a loss of dignity impacted their decision.

“These bills depend on a view that people with severe disabilities, and that includes people who are ‘terminally ill’, have such a low quality of life that they’re better off dead,” Mr Kelly said. “What these bills say is that this is a personal benefit, a social benefit. And so when people are given a pass to commit assisted suicide because of their disabilities, well, then those same views will be applied to people who are outside of an assisted-suicide situation.”

Another concerning statistic, Mr Kelly said, is the 59 per cent of people in Oregon who listed an end-of-life concern as being a burden to family members, friends, and caregivers.

“People are very susceptible to others,” he said, “and when everyone around you thinks things would be better if you were dead, well that’s going to encourage people.”

“I sympathize with people who suddenly become disabled … but that’s where we help people. We make sure that people know that they’re valued and they’re just as much of a full human being as they have ever been. It’s tragic to see people wanting to die because of shame and humiliation.

Medical aid in dying has a variety of different terms people use to describe it – including assisted suicide, physician-assisted suicide, death with dignity, and physicians aid in dying. Proponents of the legislation use terms like medical aid in dying and physicians aid in dying because the law puts the person’s terminal diagnosis as the cause of death, not the prescription drug they took.

But Mr Kelly, and other opponents, have their own reasoning for calling it assisted suicide.

“Suicide, even for sympathetic reasons, is still suicide,” he said. “The way these bills are written is that one must self-administer [the drug] … people are supposedly put in control of how they live their lives. So not to call it assisted suicide is just an exercise in euphemism.”

Denial of coverage

Oregon became the first state to pass its Death with Dignity Act, which allows a person 18 years or older with a terminal prognosis of six months or less to receive a prescription drug that would end their life. The requirements to utilise this law include the person being mentally fit, physically able to self-administer the drug, and for two doctors to sign off on the terminal prognosis.

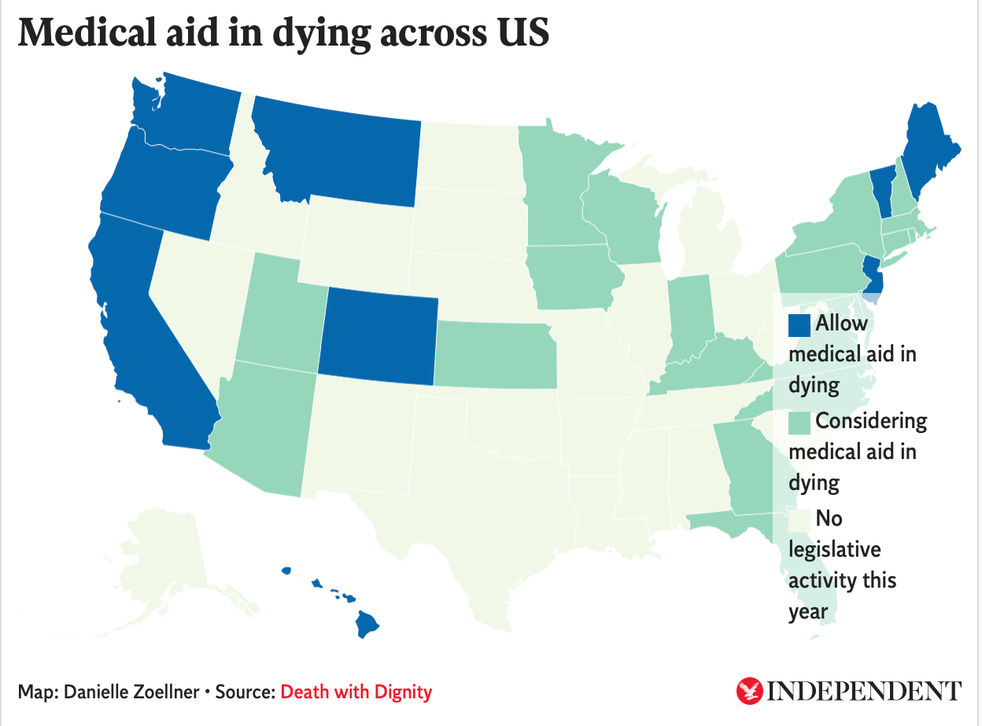

Since Oregon passed the law in 1997, other states have followed suit. Now the end-of-life option is available in California, Colorado, the District of Columbia, Maine, Montana, New Jersey, Vermont, and Washington.

Dr T Brian Callister, a board certified internal medicine and hospitalist specialist and professor of medicine at the University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine, told The Independent that the passing of end-of-life laws could limit other people’s access to care.

“What happens is that your choice for lifesaving treatment is going to be limited by the fact that the insurance companies now have a cheaper option,” Dr Callister said. He cited two cases where he sent one patient to Oregon and another to California for treatments.

“They both had serious illnesses but would not be terminal with treatment,” he said. “In fact, each patient would be curable 50 to 70 per cent of the time with treatment.”

The patients were denied care from their insurance companies and instead offered the end-of-life option, Dr Callister said.

Another case involving health insurance problems often brought up between proponents and opponents of medical aid in dying is what happened to 64-year-old grandmother Barbara Wagner.

The Oregon woman was reportedly denied coverage for her lung cancer treatment drug by the Oregon Health Plan, a Medicaid program. Instead, the Oregon Health Plan said in a letter it would cover end-of-life options, including palliative care and medication under the state’s Death with Dignity Act. Ms Wagner appealed the denial twice before the drug company producing the lung cancer treatment offered her the drug free of charge. She died three weeks later.

Opponents have said this situation proves the dangers of health insurance companies choosing the “cost-effective” route when caring for patients.

Proponents have said Ms Wagner was denied because of the drug’s “limited benefit and very high cost”, according to Death with Dignity, a nonprofit advocating for end-of-life options like medical aid in dying. The nonprofit claims “cost of end-of-life treatment” is never considered under these laws – a claim difficult to prove or disprove given the bureaucratic nature of health insurance companies.

“What happens to the prescription drugs that aren’t used?”

End-of-life laws also rely on a physician’s ability to give a patient a terminal prognosis of six months or less, an estimate Dr Callister said is often inaccurate.

“I can tell you firsthand, a physician’s ability to predict life expectancy in terminal illness is often not accurate at all,” Dr Callister said.

In a 2016 systematic review of various studies looking into prognostic accuracy, it found accuracy by doctors spans from 23 to 78 per cent. In addition, survival estimates tend to range in three months shorter from the doctor’s prognosis to three months longer.

Oregon’s 2019 annual data summary found that 188 people took the prescription medication to end their life after requesting it through their doctor. Of those 188 people, 18 of them had received the medication in previous years, proving how patients can sometimes live past their terminal prognosis of six months or less.

“What really concerns me, though, is what happens to the prescriptions that aren’t used? These are obviously deadly drugs and roughly one-third of these prescriptions go unused,” Dr Callister said.

Once a patient receives the prescription from their local pharmacy, there is no requirement for a healthcare professional to be present when the medication is taken by the patient. In 2019, 290 people received prescriptions under Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act, but only 188 actually took the drug. Of the 290 people, 62 recipients of the prescription decided not to ingest it and subsequently died from other causes.

“There’s no mechanism for tracking that these are in medicine cabinets somewhere,” Dr Callister claimed.

Since these medications fall under the category of a Schedule II drug under the Controlled Substance Act, they are under federal statutes. This means the medication must be taken by whomever it was prescribed to and people could face criminal prosecution if it’s taken by someone else.

States like California, for example, require people who have custody of “unused aid-in-dying drugs” to “personally deliver the unused aid-in-dying drugs for disposal by delivering it to the nearest qualified facility that properly disposes of controlled substances” or dispose of it by “lawful means in the accordance with guidelines promulgated by the California State Board of Pharmacy.”

Physicians and pharmacists are also required to report prescribing and selling the medications to patients, but the law does not require additional follow-up once the patient has possession of the drugs.

Another requirement under the end-of-life laws is for two physicians to sign off that a patient has a terminal prognosis. Physicians are allowed to opt out of assessing a patient for an end-of-life option, as they might believe it goes against the oath they took to save lives.

“The American Medical Association (AMA) has reiterated that physician-assisted suicide is fundamentally incompatible with the physician’s role as healer,” Dr Callister said, referencing a 2016 opinion piece published by the AMA on the subject matter.

The AMA’s House of Delegates voted in June 2019 to maintain the organisation’s long-held opposition to the end-of-life option.

“It is understandable, though tragic, that some patients in extreme duress — such as those suffering from a terminal, painful, debilitating illness — may come to decide that death is preferable to life. However, permitting physicians to engage in assisted suicide would ultimately cause more harm than good,” the AMA wrote in its opinion piece.

Despite its staunch opposition to the laws, the state AMA chapters of California, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nevada, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington all have moved into a neutral position.

A 2018 Medscape survey of 5,200 physicians across the US found that 58 per cent agreed medical aid in dying should be available to terminally ill patients, which was up 12 per cent from 2010. Additionally, 74 per cent of Americans think the end-of-life option should be available, according to a 2020 Gallup poll.

Impact on suicide across America

Although patients are required to be mentally fit when applying to take the prescription, concern has mounted on if the safeguards in place actually prevent those who suffer from depression or mental health problems from utilising the law.

In Oregon, for example, only one patient was referred psychological or psychiatric evaluation in 2019. This number is consistent with all of Oregon’s data since the law was enacted, with a vast majority of patients never receiving a mental health evaluation.

“If you’re terminally ill, it is quite reasonable to understand that you’re going to go through all kinds of feelings, including grief feelings, and the chance of you becoming clinically depressed is certainly going to be higher than if you weren’t terminally ill,” Dr Callister said, emphasising the importance for these patients to be clinically assessed before accessing end-of-life options.

“Being depressed is a natural part of what we will call a reactive grief,” he added. “We have to look at from a public policy perspective and ask if there is a suicide contagion that comes with legalised assisted suicide.”

Oregon’s suicide rate per 100,000 residents was 16.03 per cent in 1998 and has since risen to 19.6 per cent in 2019. People dying under the Death with Dignity Act are not included in these figures.

The national suicide rate has also risen in that time period, from standing at 11.12 per cent per 100,000 people in 1998 to rising to 14.2 per cent in 2018.

It would be difficult to determine how much Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act has played into the rise of the state’s suicide rate, but the rate is 35 per cent higher than the national average, according to a study by the Oregon Public Health.

Coercion and abuse

Ultimately the largest concern brought up against the passing of these laws is coercion on the part of the physician, insurance companies, or patient’s family members and friends that could convince someone to take the medication.

Proponents have argued there are limited reports of abuse in all states with the end-of-life-option. But with healthcare professionals present during less than one-third of these deaths plus few patients being referred for psychiatric evaluations, the proponents claim is shrouded in uncertainty.

Kathryn Judson, an Oregon resident, wrote a letter to the editor in the Hawaii Free Press in 2011 to explain her opposition to the passing of medical aid in dying.

“When my husband was seriously ill several years ago, I collapsed in a half-exhausted heap in a chair once I got him into the doctor’s office, relieved that we were going to get badly needed help (or so I thought),” she wrote.

“To my surprise and horror, during the exam I overheard the doctor giving my husband a sales pitch for assisted suicide. ‘Think of what it will spare your wife, we need to think of her’ he said, as a clincher.”

She saw the conversation as coercion on the part of the physician, and she and her husband, David, sought out a different doctor about their options for his illness. David lived an additional five years after that interaction.

“I think despite the best intentions to alleviate suffering, these laws are creating horrible, negative consequences,” Dr Callister said.

He advocated for focusing on improvements to palliative care, hospice care, and social services for patients over passing end-of-life laws.

“We don’t need these laws … because we can control your symptoms at the end of life,” he said.

Source: independent.co.uk